An overview of the 1916 Rising

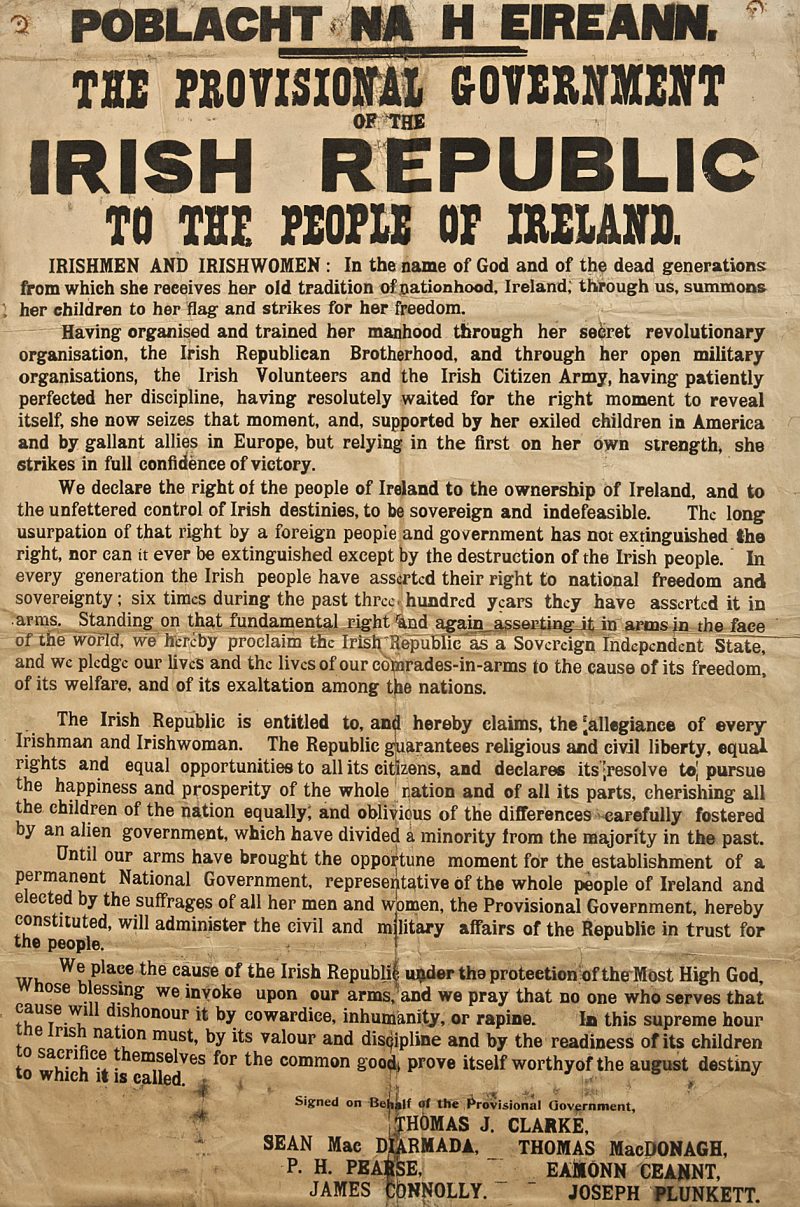

Around midday on Monday 24 April 1916, Patrick Pearse read a proclamation on behalf of the ‘Provisional Government of the Irish Republic’ at the front of the General Post Office on Dublin’s Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street). This marked the symbolic opening of what is now most commonly referred to as the Easter Rising (the British referred to it as a ‘rebellion’ or ‘insurrection’). That day, over 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers, Irish Citizen Army, Hibernian Rifles and Cumann na mBan occupied a series of buildings around Dublin city, as well as a public park at St. Stephens’ Green. The GPO became rebel headquarters and the base for five of the seven men who had signed the proclamation.

The Rising was planned and executed by—as historian F. X. Martin put it—‘a minority of a minority of the minority’. The ‘military council’ who led the planning were made up members of the underground revolutionary Irish Republican Brotherhood, hand-picked by veteran Fenian Thomas Clarke and his protégée Seán MacDermott; socialist and leader of the much smaller Irish Citizen Army, James Connolly, was also added to the conspiracy. The conspirators kept their plans secret from any fellow members of the IRB likely to oppose them and, most notably, from the chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers, Eoin MacNeill.

To the surprised citizens of Dublin and the administration in Dublin Castle, the rebels were seen as ‘Sinn Feiners’, a blanket term applied to extreme nationalists, though Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin was not involved. The outbreak of violence on the streets of Dublin provoked a mixture of confusion, derision, anger, and hostility. A limited form of Irish Independence, with which most of the nationalist community was satisfied, was already on the statute books with the Government of Ireland Act, postponed until the end of the current European war.

Dublin City Centre in the immediate aftermath of the 1916 Rising

Many in the city had relatives—fathers, husbands, brothers—fighting with the British army, some of whom believed they were fighting for Home Rule or who had been members of the Irish Volunteers before the organisation split in 1914. For those men, and many others, the Rising was at best a foolish enterprise and at worst a betrayal. The daily life of the city was monumentally disrupted during the fighting, with access to food, money, and supplies, and the disruption to businesses—along with the increasing civilian casualty figures (which made up about half of the Rising’s fatalities by the end of the week)—causing panic, anger and fear.

Within a week, the rebels had been defeated and rounded up. By 12 May, fourteen of the leaders had been executed in Kilmainham Gaol (including the seven signatories), and another in Cork. Roger Casement, arrested in Banna Strand, County Kerry, on the eve of the Rising, was hanged in London in August. Around 3,500 men and women were arrested. Many were quickly released but over 2,000 were interned and deported to prison camps in England, Scotland, and Wales.

Though the Rising may have failed militarily, it was a huge symbolic victory. The scale of the executions and arrests in particular saw a gradual and complex, but significant, shift in public opinion in favour of the rebels: the ‘republic’ became the prominent nationalist aim. The Rising is now regularly considered as one of the pivotal moments in modern Irish history and the key starting point on the road that eventually led to independence for twenty-six Irish counties in 1922. Events like those around Northumberland Road and Mount Street Bridge have added to the endurance of the myth that very quickly formed around the Rising.

Destruction of Dublin City Centre

The images below from the Westropp Collection of the Royal Irish Academy were taken by Thomas Johnson Westropp in May 1916 and show the wide scale destruction of Dublin city centre caused by the British bombardment of the areas held by the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army.